This essay is part of a series exploring the concept of Integrated Law, a new service category in the legal industry that addresses a key challenge facing in-house counsel: Complex Legal Work at Scale. Today, we look at complexity in the legal industry: the myth behind it that has misdirected innovation efforts, its three flavors and how it is increasing in our industry.

Lawyers are undoubtedly masters of complexity. As we saw in our previous essay, as the business world has evolved, so too has the legal industry. As companies became more internally complicated and faced a more externally complex environment, the legal solutions available to them developed to handle this.

But, at the same time, our treatment of complexity itself has been simplistic.

The focus of much legal innovation effort has been based on a simple myth: that legal work gets rarer as it gets more complex. We’ve ignored the fact that complexity is not a single, simple metric. And we’re increasingly in a world where even routine work is becoming more complex.

The Myth of Commoditization

Much of the discussion around the innovation of legal work follows a simple logic when it comes to complexity. Namely, that there is a (meaningfully large) core of legal work that is so simple it can be readily commoditized. Much legal innovation in the form of legal tech and new law providers aims to relieve in-house departments from the drudgery of this rote, commoditized work, thereby freeing them up to do higher value-added work.

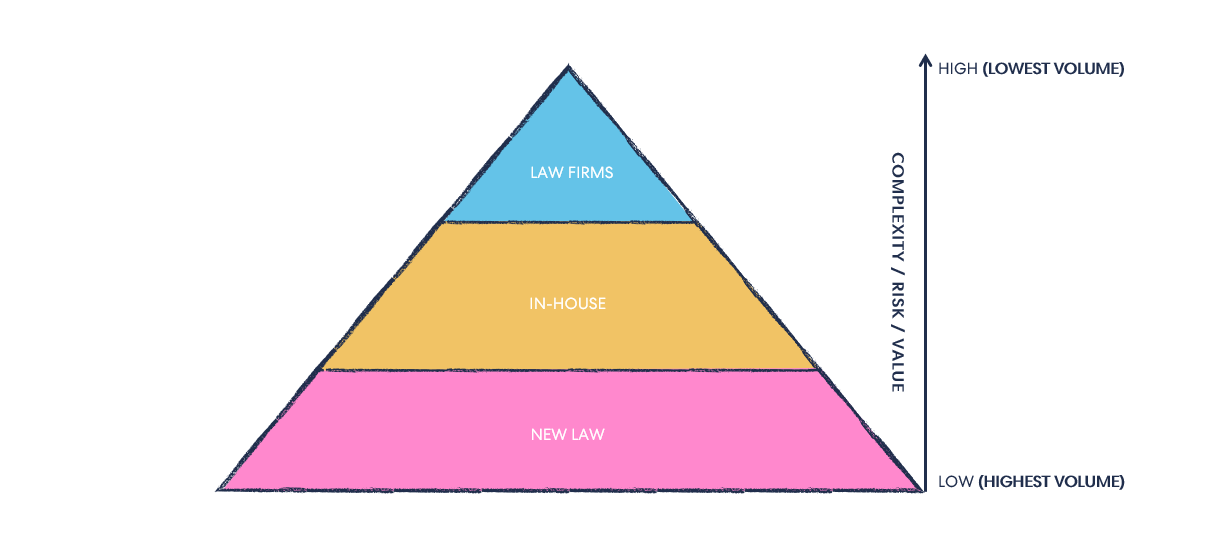

The problem is that most of the work in-house departments confront isn’t commoditized or readily commoditize-able. In this view, it’s not that legal innovation efforts have failed but rather that they’ve been aimed at the wrong target: the simplest work, wrongly believed to be the most abundant. This misconception is well represented in the oft-used depiction of the legal provider ecosystem as a pyramid, in which the rarest work is shown to be the most complex and the most common work to be the simplest.

Despite its familiar presence in various forms, this depiction just isn’t accurate. Most in-house lawyers would tell you that the bulk of the work they confront isn’t the simplest. It may not be once-in-a-career matters of first impression, worthy of the best legal minds on the planet, but it’s not mindless drudgery either. Perhaps the only part of the legal industry where a genuinely meaningful quantity of work has been commoditized is ediscovery. Unbundling, outsourcing, and technology enablement have indeed removed the drudgery of high-cost lawyers wading through reams of material, allowing it to be churned out in a commoditized manner. Were the myth of commoditization factual, we would expect significantly more of the work that in-house teams undertake to be capable of similar treatment.

By contrast, outside of ediscovery, we see something very different. Rather than work that is increasingly standardized and capable of commoditization, we see that work is growing in its complexity as businesses operate in more complicated internal (think internal compliance, approval and systems requirements) and external (think globalization, new regulations, and supply chain security etc.) environments with the added pressure of demands for greater velocity.

We see the effects of this in the increased growth of in-house teams, which has massively outpaced that of big law in recent years, both in terms of absolute numbers and the increasing seniority of in-house lawyers. This shows us that there is a significant workload in in-house teams of growing and recurring complexity.

The increasingly inaccurate assumption of commoditization matters as the idea of solving for ‘bottom of the pyramid’ work has been at the heart of the ALSP and LegalTech sectors. Based on this assumption, billions have been invested, but 20+ years in, the legal innovation industry is still more talk than impact. All the well-intentioned (and occasionally well-funded) innovation in the world can’t deliver impact if it’s aimed at the wrong target.

The Flavors of Complexity

As we saw in our previous essay, by about 2010 we had settled into three models of legal services delivery: law firms, in-house and new law providers. Alongside this, we also developed a view of complexity as a sort of proxy for the risk or value of any individual piece of legal work.

At the highest end of this conception of complexity was the infrequent “bet the company” tasks, the sort of things that represented existential challenges for the company. This work went to law firms. After this, there was a layer of valuable recurring work that stayed inside the company with the in-house team. Finally, there was the grunt work. The type of work that, though voluminous, didn’t represent particular risks to the company and simply needed a lot of heads to get it finished. This ended up going to new law providers.

However, this view is myopic. Rather than a single vague notion of complexity as a shadow of risk or value, the truth is that complexity in our industry has multiple flavors.

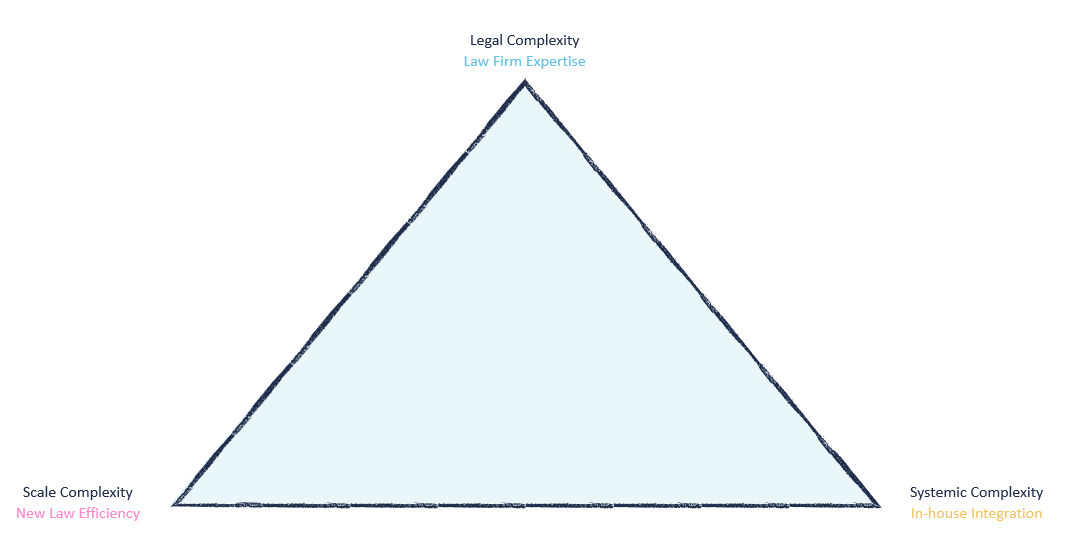

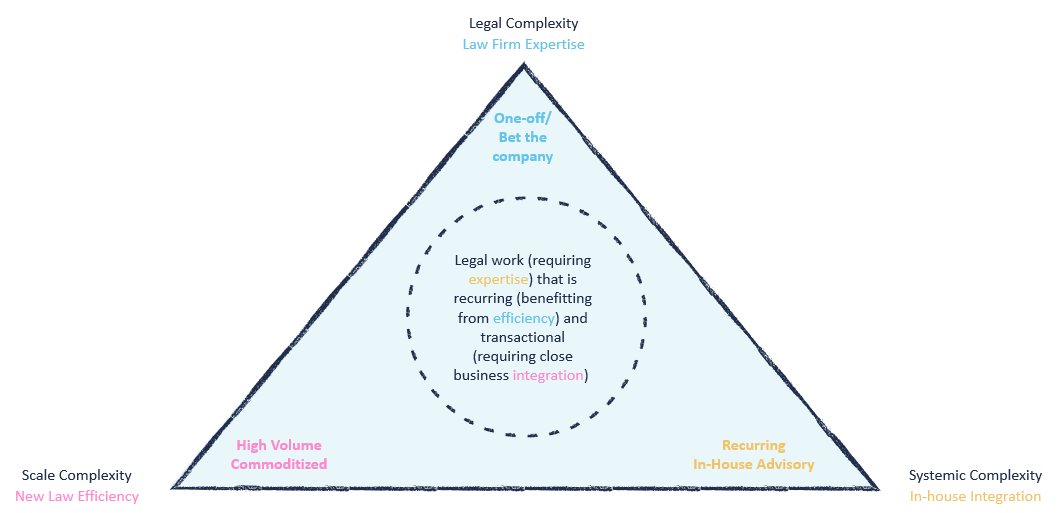

Inspired by Jae Um’s division, we distinguish three types of complexity: legal, systemic, and scale. Different legal work always sits at the intersection of these, with differing levels of each type of complexity. Also, importantly, high complexity is not the sole preserve of law firms. Rather, each type of provider in the legal services industry specializes in handling one of these types of complexity.

Legal Complexity

Legal complexity is a measure of the complexity we encounter caused by the interplay between the situation at hand and the relevant legal framework. This can range from clear-cut everyday cases to those that are much more nuanced: think of the difficulty of addressing a completely new regulation or undertaking a transaction that may trigger competition law.

The response to legal complexity is expertise. As we saw in our survey of the history of the legal profession, the development of large law firms was tied to the development of a broad base of knowledge across specializations. To this day, high legal complexity is the type of complexity to which law firms cater most effectively.

Systemic Complexity

This is the type of complexity that arises from the systemic requirements of a modern business with the interplay between legal work and numerous stakeholder groups, internal systems and business processes. In-house legal work doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It happens in the real (and often messy) world of a big company. Navigating this messy reality brings its own complexity, distinct from the legal substance itself. This systemic complexity calls for deep integration with the business in order to master its systems, processes and stakeholder environment. This is the natural domain of the in-house legal team with its close interactions with and deep understanding of the business.

Scale complexity

The final type of complexity that arises is caused by the volume of legal work. The skill that most closely tracks this is efficiency, particularly the efficiency that arises within new law companies that use technology and smart resourcing to tackle large-scale challenges like litigation discovery or massive document reviews.

This leaves us with a very different triangle of what complexity looks like in the legal sector. Rather than a single axis, it’s the combination of these three flavors of complexity.

The Messy Middle: Complex Legal Work at Scale

So, if all legal work maps to these types of complexity to a different degree and each of the existing market providers specialize in one of these types of complexity only, what does this mean for the work that sits somewhere in the middle of these types of complexity? That is work that requires some expertise to address legal complexity, which occurs regularly enough (with enough scale) that efficiency matters and takes place in the complex context of a large company, requiring close integration to navigate internal systems, processes and stakeholders. This is what we call “Complex Legal Work at Scale”, work which isn’t commoditized despite there being lots of it. This work, of which BAU contracting is the most prominent, most prevalent example represents the gap that’s been left unaddressed by two decades of legal innovation.

What does this mean for in-house legal teams?

As we’ve seen, complexity is not a simple matter in the legal industry but rather a blend of characteristics. What’s more, we now see that the level of complexity is not static nor even increasing in a linear fashion but accelerating exponentially. The challenge for in-house teams is not only to address the difficulties that they face today but to build solutions in a way that addresses the underlying cause of the growing complexity in their work: the increasing prevalence of Complex Legal Work at Scale. We will see in the next essay in this series the scale of this challenge and why the existing providers of today have not addressed it.