This essay is part of a series exploring the concept of Integrated Law, a new service category in the legal industry that addresses a critical challenge facing in-house counsel: Complex Legal Work at Scale. Today, we look at this uncovered space and the scale of the problem it represents. We also look at why current market providers are not adequately equipped to provide relief.

In 1999, NASA lost its Mars Climate Orbiter (and the $300 million spent on the mission) when a key operation failed because no one realized that two key pieces of software designed by NASA and Lockheed Martin used different units. The former used metric, while the latter used US units, leading the Orbiter to crash violently into the Martian atmosphere. The point is it's vital to make sure you’re using the same scale to solve a problem, especially when you’re dealing with something novel.

As we’ve already seen in this series, the misunderstanding of complexity in the legal market has led us to misdirect our efforts for decades. In this essay, we’ll refine our understanding of Complex Legal Work at Scale in a way that keys in on the predicament facing in-house legal. We’ll then use this definition to estimate how much of in-house spending is composed of Complex Legal Work at Scale. Finally, we’ll address the key question of why the current providers in the market are not adept at addressing the challenges that Complex Legal Work at Scale presents.

What do we mean by Complex Legal Work at Scale?

As we saw in the previous post in this series, the work that preoccupies in-house counsel and where they most need relief is not simple, commoditized work. Rather, the greatest challenge posed to in-house counsel is by work that sits at the intersection of three types of complexity:

Legal Complexity – The traditional notion of complexity caused by the interplay of the situation at hand and the law. The answer to this type of complexity is expertise.

Scale Complexity – The type of complexity that arises from the volume of work entailed. The answer to this type of complexity is efficiency.

Systemic Complexity – The type of complexity that arises from the fact that alongside legal considerations, in-house systems, processes and stakeholders must also be navigated. The answer to this type of complexity is close integration with the business.

The work that sits at the “messy middle” intersection of these three types of complexity is what we call “Complex Legal Work at Scale”, meaning that solving for it requires expertise, efficiency, and close integration with the business. The most prominent, most prevalent example of this work is recurring transactional work like contracting.

(Many) Tens of billions of dollars in Complex Legal Work at Scale?

The fact that this problem has gone unnoticed for so long is more baffling when we look at the scale of spending it represents.

Firstly, legal spend inside organizations tends to function as a percentage of revenue. This varies by industry (more for regulated industries such as banks) and geography (a little skewed by the notoriously litigious US), but in general, it represents the relative cost of doing business. The median value for this across large businesses globally is 0.56% of revenue.

Let’s keep things simple and narrow our focus to a subset of organizations. If we take the Forbes 2000 list of the top 2000 public companies globally, we see that last year they generated revenue of $47.6 trillion. If we applied the 0.56% metric to this, then we’re left with a $266.6 billion dollar bill for legal services among these companies alone.

We then further see that we can split this between their internal and external spend. In 2022, this internal spend outstripped external spend for the first time at 54%. Further proof, were it needed, that there is a growing level of routine work that in-house counsel must face. If we apply this split to our $266.6 billion figure, this gives us a figure of $143.9 billion spent on in-house counsel by these 2000 companies alone.

Then we come to the question of how much of this estimate represents Complex Legal Work at Scale. Let’s take contracting as the epitome of this work. According to FTI, the majority of legal departments spend more than 30% of their time on contracting work. Our experience of this suggests that, at most, 25% of this work is commoditized. The remaining 75% is the kind of routine, recurring work that we call Complex Legal Work at Scale. That’s more than $32.3 billion spent on the in-house contracting component of Complex Legal Work at Scale in these 2000 companies alone.

Of course, this isn’t a perfect figure. It’s limited to those companies where Complex Legal Work at Scale will be most pronounced, for whom complicated legal work is a cost of achieving their impressive revenue, but it excludes the thousands of smaller businesses it also impacts. Similarly, not all Complex Legal Work at Scale is currently handled internally. Some of it is handled imperfectly by external providers who are unsuited to its completion. All this aside, this gives us a sense of the scale issue.

Why existing market players have failed to solve for this?

Why, then, if so much of in-house spend, not to mention the attention of in-house counsel, is absorbed by Complex Legal Work at Scale, do current market players not solve for this? The simplest answer is that they weren’t designed to.

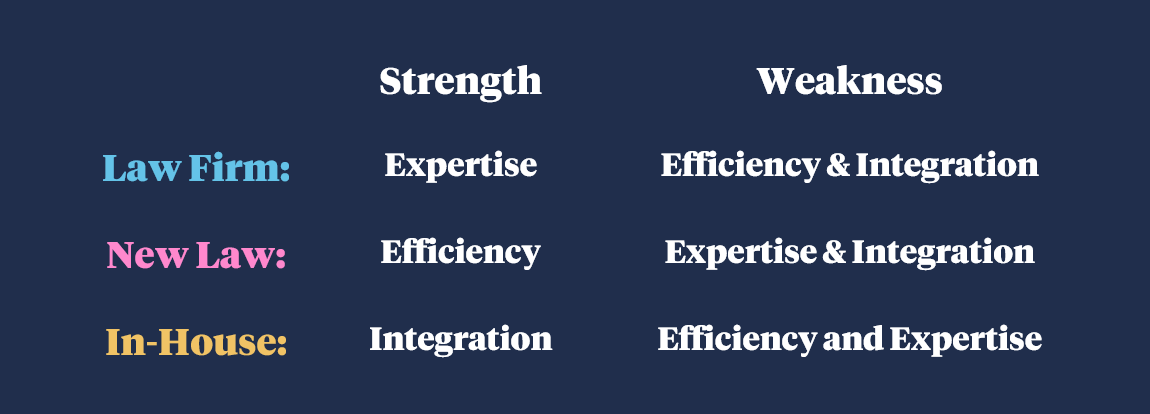

As we looked at in our first essay, each generation of service providers in the legal services market emerged in response to a particular need that evolved in the business world. In this sense, each developed a superpower. For law firms, this is expertise; for in-house counsel, it’s integration; for new law: efficiency. Each category of service provider also has in-built structural limitations that prevent it from investing in and developing certain strengths. These structural limitations match their respective superpowers with something akin to their kryptonite.

Consider a law firm. In-house teams turn to their external counsel for deep and broad expertise that they don’t possess internally. Full-service law firms have long catered to this by increasing the breadth and depth of the markets, industries, and practice areas that they cover. However, their business models have limited their desire and ability to develop and invest in the drivers of efficiency.

The same goes for new law. Designed with an eye to the myth of commoditization we have previously explored, efficiency has long been the goal with process, technology, and smart staffing. With low rates forming a key element of their value proposition, these providers struggle to incorporate a significant contingent of senior legal expertise into their offerings.

Similarly, when we look at in-house counsel. While a deep integration with the goals of the business has long been the raison d’etre for GCs, investing in the drivers of efficiency is typically limited by their status as cost-centers. Because they tend to cover two of three requirements (expertise and integration), Complex Legal Work at Scale, like contracting, has largely fallen to in-house departments. Given limited budgets and bandwidth, this work often comes at the expense of more time spent on what is the highest and best use of in-house teams, the sort of advisory that really pushed the business forward.

The truth is that because no one has specifically identified this space of Complex Legal Work at Scale, no one was building a comprehensive capability set that would be required to address it. That’s where a new approach is needed. A new set of solutions. We believe the answer to this is Integrated Law, and in the next essay, we will explore the skillsets that compose this new service category.